- Home

- Kirsten Gillibrand

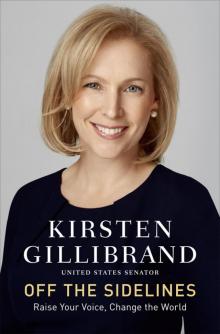

Off the Sidelines

Off the Sidelines Read online

“Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s story will prove instructive to anyone who wishes to find her true north, understand power dynamics, and confront entrenched interests when justice is not served. Off the Sidelines is required reading for all women who want to change the world and recognize that to do so they must better understand political realities.”

—PIPER KERMAN, author of Orange Is the New Black

“Reading Kirsten’s book makes me so proud—as a woman, as an American, and as her friend. She is a beautiful example of what we can become when we are true to ourselves and brave enough to let our voices be heard. This book is intimately honest and deeply insightful. It should be on every girl’s and every woman’s reading list, and every boy’s and man’s, too.”

—CONNIE BRITTON

“Kirsten Gillibrand is one of the most forward-focused leaders we have working on our behalf, and Off the Sidelines is an excellent example of inspiring women to make their voices heard.”

—BILLIE JEAN KING

“A must-read for every woman looking to effect change. Gillibrand’s secrets to speaking up—whether you’re striving for political office, aiming for the boardroom, or simply trying to improve your kid’s school—are powerful lessons for women looking to make a difference. After all, if you’ve worked hard enough to gain a seat at the table but you say nothing, that’s a lost opportunity.”

—URSULA BURNS, chairman and CEO, Xerox Corporation

“Senator Gillibrand is a vibrant role model for her generation and makes a strong and very personal case for why we should all care about our government. Her trademark honesty and humor speak loudly to why we need women in the game.”

—GERALDINE LAYBOURNE, founder, Oxygen Media and Kandu

As of press time, the URLs displayed in this book link or refer to existing websites on the Internet. Penguin Random House LLC is not responsible for, and should not be deemed to endorse or recommend, any website other than its own or any content available on the Internet (including without limitation at any website, blog page, information page) that is not created by Penguin Random House.

Copyright © 2014 by Kirsten Gillibrand

Foreword copyright © 2014 by Hillary Rodham Clinton

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

BALLANTINE and the HOUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Gillibrand, Kirsten.

Off the sidelines: raise your voice, change the world / Kirsten Gillibrand with Elizabeth Weil.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-8041-7907-2

eBook ISBN 978-0-8041-7908-9

1. Gillibrand, Kirsten. 2. Gillibrand, Kirsten—Philosophy.

3. Women legislators—United States—Biography. 4. Legislators—United States—Biography. 5. United States. Congress. Senate—Biography.

6. Women—Political activity—United States. 7. United States—Politics and government—1989– I. Weil, Elizabeth. II. Title.

E901.1.G55A3 2014

328.73′092—dc23 2014024020

[B]

www.ballantinebooks.com

Jacket design: Joseph Perez

Jacket image: Rainer Hosch

v3.1

FOREWORD

Hillary Rodham Clinton

The first time I shook Kirsten Gillibrand’s hand, she looked me square in the eyes and said, “How can I help?” I was running for Senate in New York and Kirsten wanted to do everything she could for the campaign. But there was more to it than that. Kirsten has built her whole life around the question “How can I help?” Wherever there’s a problem to solve, a wrong to right, or a person in need, Kirsten rolls up her sleeves and gets to work. Staying on the sidelines just isn’t in her DNA. That’s been the story of her entire career—as a lawyer, then as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives, and now as a U.S. senator—and it’s the story of this book.

Off the Sidelines is a memoir of a life shaped by a deep commitment to family, public service, and hard work—and a story that is far from finished. I hope it will serve as an inspiration to others, especially young women, and encourage them to follow Kirsten’s example. The health of our democracy depends on women as well as men stepping off the sidelines to participate—to vote, debate, organize, run for office, and lead.

Kirsten wasn’t born a senator, but service is in her blood. Her story starts with another indomitable woman: her grandmother Polly Noonan. At a time when few women were involved in politics, Polly was a force. She was a fixture in Albany and a role model for Kirsten. On weekends, Kirsten stuffed envelopes and slapped bumper stickers on cars, getting her first taste of political participation. Kirsten’s mom, Polly Rutnik, was a trailblazer, too—a lawyer, one of the first working moms in the neighborhood. You can see the influence of these women throughout Kirsten’s life. Just as Polly often made dinner while balancing a phone on her shoulder, conferring with clients, it’s not unusual to find Kirsten on the Senate floor, casting a vote, with one eye on her small sons, waiting for their mom in the hallway just outside. And this is one of the lessons found in Off the Sidelines that resonate far beyond Washington. Women across our country work hard every day to juggle the demands of work and family. Sometimes it can seem as if we have to give up one dream in order to pursue another. But Kirsten shows us how much is possible. Women can lift up themselves, their communities—even entire countries. All they need is a fair shot and the chance to participate.

When I accepted President Barack Obama’s offer to serve as secretary of state, I wanted someone strong and caring to fill my seat in the Senate. From 9/11 to the financial crash, it had been a rough eight years for New Yorkers. They had taken a chance on me back in 2000, and now they needed an effective and committed advocate in Washington.

Kirsten was a great choice. As a congresswoman, she was a champion for families in her upstate New York district and a creative problem solver willing to reach across the aisle to get the job done for her constituents. And she was a leader on transparency, putting out a weekly “Sunlight Report” detailing exactly how she spent her time. The New York Times called it “a quiet touch of revolution.” She was just what the Senate needed. A few days before she was sworn in, Kirsten and I sat down for lunch with Governor David Paterson and Senator Chuck Schumer. She told us, “I’m going to hit the ground running.” And boy, did she. Practically overnight, Kirsten went from a junior congresswoman to a prominent and powerful senator.

I was particularly pleased that she continued the fight for one of my most deeply held personal priorities: standing up for 9/11 first responders and others who had suffered lasting health effects from their service around Ground Zero. And that wasn’t all. No one has been a stronger champion than Kirsten for victims of sexual assault within our military—an issue that’s too often been put on the back-burner or put off altogether. And she’s stayed true to her roots, continuing to advocate for upstate New York and working to create jobs and opportunities across the state. She’s even co-captain of the Congressional softball team!

Above all, Kirsten gets results. She has no time for the dysfunction and gridlock that hamstring Washington. We need more leaders like Kirsten, willing to choose common ground over scorched earth.

Like most women who have run for office, Kirsten’s faced her share of challenges. Instead of letting those obstacles stand in her way, she’s made it a personal mission to help the women coming up behind her. She was just the sixth woman to give birth while in Congress—showing everyone once again that it’s possible to be a great mom and a dedi

cated public servant. In fact, being a mom can make you an even better public servant.

For Kirsten, public service isn’t a job. It’s a calling. She sees people suffering, or being mistreated—people who aren’t getting the shot they deserve, who have the talent and the work ethic but not the opportunity—and she asks the same question I first heard all those years ago. “How can I help?” It’s who she is. It’s how she’s made. And it’s what makes her a great senator, and a great friend.

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

FOREWORD BY HILLARY RODHAM CLINTON

INTRODUCTION

Chapter 1: I’m One of Polly’s Girls

Chapter 2: From A to B, with Detours

Chapter 3: So What If the Cows Outnumber Your Supporters?

Chapter 4: The Best Lobbyist I Ever Met Was a Twelve-Year-Old Girl

Chapter 5: Let’s Clean Up the Sticky Floor

Chapter 6: Ambition Is Not a Dirty Word

Chapter 7: Now We’re Yours

Chapter 8: “You Need to Be Beautiful Again,” and Other Unwanted Advice

Chapter 9: Be Kind

Chapter 10: My Real Inner Circle

Chapter 11: A Time Such as This

Chapter 12: Get in the Game

Photo Insert

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Resources

About the Author

INTRODUCTION

If I had a daughter, I would tell her certain things. I would tell her that it’s great to be smart, really smart—that being smart makes you strong. I would tell her that emotions are powerful, so don’t be afraid to show them. I would tell her that some people may judge you on how you look or what you wear—that’s just how it is—but you should keep your focus on what you say and do. I would tell her that she may see the world differently from boys, and that difference is essential and good.

These are not the lessons I feel I need to give my sons. They already believe that they are innately strong and powerful and that others will respect their worldview. This hit me when my younger boy, Henry, was two and a half years old, and my husband, Jonathan, took him and Theo, his older brother, then age seven, to Theodore Roosevelt Island to explore. Roosevelt Island is fantastic: right in the middle of the Potomac River and filled with woodpeckers, frogs, marshes, trails, and a seventeen-foot statue of Roosevelt himself, in shining bronze and larger than life. Along one of the paths, the kids came to a hill. Jonathan, sensing a slowdown and not wanting to carry Henry, said enthusiastically, “Come on, boys!”

Henry didn’t miss a beat. He just nodded his little chin in agreement and said, “We can do it because we’re men!”

Now, I love my sons, and I love Henry’s confidence. I want him to think that the world is his. But how the hell did he come to believe, at the tender age of two, that he could do anything because he is a (very little) man? I did not teach him this. In our family, capability has nothing to do with gender. I’m one of only twenty female senators, so I have about as atypical a job as you can find for a woman in the United States. More to the point, how many girls in his preschool class, when faced with some hill to climb, would say brightly, “We can do it because we’re women!”?

I can tell you how many: zero. Well, maybe one, Irina—more on her later. That’s why I’m writing this book. I want women and girls to believe in themselves just as much as men and boys do. I want them to trust their own power and values and say, “We can do it because we’re women!”—not just for their own sense of self, but for all of us. Girls’ voices matter. Women’s voices matter. From Congress to board meetings to PTAs, our country needs more women to share their thoughts and take a place at the decision-making table.

This is not a new idea. During World War II, Rosie the Riveter called on women to enter the workforce and fill the jobs vacated by enlisted men. The Rosie the Riveter advertising campaign had a simple slogan: We can do it! And she told women two things: One, we need you, and, two, you can make the difference. My great-grandmother Mimi and my grandmother’s sister, my great-aunt Betty, both saw Rosie on posters, pulled off their aprons, and headed to work at an arsenal in Watervliet, New York, assembling ammunition for large weapons. Throughout my childhood, lamps made out of shell casings from that arsenal lit my great-grandmother’s living room. Rosie the Riveter was direct, unconventional, and extremely effective. By the end of the war, six million women, including my great-grandmother and her daughters, worked outside the home. Their generation forever changed the American economy and women’s role in it.

We need a Rosie the Riveter for this generation—not to draw women into professional life, because they are already there, but to elevate women’s voices in the public sphere and bring women more fully into making the decisions that shape our country.

I first realized this as an eager twenty-eight-year-old who looked up from her law firm work long enough to notice that First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton was speaking to the world from a stage in Beijing. She was at the United Nations World Conference on Women, and she was delivering to the whole planet a very simple, powerful message: Women’s rights and human rights are one and the same. I was floored. I’d majored in Asian studies at Dartmouth and studied Mandarin in Beijing. I couldn’t believe Hillary was so bold as to make that speech from China, where the women’s rights movement was decades behind the one in the United States. I kicked myself for not being there, for not even knowing about the conference. That woke me up to the fact that there was an important global conversation taking place. I cared deeply about it, and I wasn’t participating.

What was I waiting for? An invitation? Thanks to my grandmother Polly, who was involved in Albany politics, I grew up steeped in political stories—it was simply background noise in our family. When I was young, maybe six or seven years old, I sat around with my little sister, Erin, and my cousin Mary Anne, and while they announced that they wanted to be an actress and a flight attendant when they grew up, I said I wanted to be a senator (not that I knew what a senator did, exactly, but I knew it sounded accomplished and important). Yet by high school I’d lost my girlhood bravado. I knew by then that my goal sounded presumptuous for a girl, so I switched to saying I wanted to be a lawyer. But when I heard about Hillary’s address in Beijing, my unfiltered childhood sense of self came rushing back. I wanted so badly to have been there in Beijing—and that meant I needed to become more involved in politics. I needed to embrace the part of me that I’d been pushing away.

At the time, I was living in a small apartment with my actress younger sister on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, working far too many fifteen-hour days. Outside work, I was volunteering with a few local charities, trying to make a small difference. But politics was something I hadn’t touched since I was a kid, helping my grandmother and her friends elect local candidates. So I called a friend’s mother, who had worked for Vice President Gore doing children and family policy, for advice about getting involved. I trusted and respected her, so when she recommended joining the newly formed Women’s Leadership Forum, a political fundraising group for women who cared about presidential politics, I did.

A few weeks later, I left my law office early one evening and headed over to the River Club, a few blocks from the Queensboro Bridge, to hear the first lady speak. Nervous and excited, in my best blue suit, I stood in the back of the room. I was exhausted from the treadmill of my life, I was by far the youngest of the hundred women in the room, and I didn’t know a soul. But Hillary Clinton said something that changed me: “Decisions are being made every day in Washington, and if you are not part of those decisions, you might not like what they decide, and you’ll have no one to blame but yourself.”

She didn’t know me any better than a potted plant. She wasn’t even looking in my direction. But inside I felt singled out. I cleared my throat and started sweating, knowing right then that I needed to alter my life. I was on track to make partner at a big corporate

law firm, which would mean a healthy paycheck, more than enough to raise a family someday. But there, in that room, for the first time, I was forced to confront that this wasn’t what I wanted for myself. I wanted to do work that mattered to me. I wanted to help shape decisions that impacted people in positive ways. I wanted a life in public service. The idea of running for office terrified me, but deep down I knew I had to. The first lady was right: If women in all stages of life don’t get involved and fight for what we want, plans will be made that we may not like, and it’ll be our own damned fault. I think about this every day. It’s true at every level, from the Capitol to your city’s town hall to your neighborhood school. We need to participate, and we need to be heard. Our lives, our communities, and our world will be better for it.

It’s almost twenty years later, and I’m still fighting for women to be heard. The landscape for women in politics right now is not pretty. As Gloria Steinem said, brilliantly, “The truth will set you free. But first it will piss you off.” So here’s my blunt truth: I’m angry and I’m depressed, and I’m scared that the women’s movement is dead, or at least on life support. Women talk a lot these days about shattering the glass ceiling, but we also need to focus on cleaning the so-called sticky floor, making sure all women have a chance to rise.

Americans need to demand change. Ours is the only nation in the developed world with no paid maternity leave. We have no paid family sick leave. We don’t ensure affordable daycare, or provide universal pre-K, or mandate equal pay for equal work. And what do we do when our representatives fail to fight for these things? Nothing. No axes drop. No booms come down. We do not hold our representatives accountable. When politicians fail to serve constituents on Second Amendment rights or farm subsidies, do you think those voters remain quiet? Not a chance. They respond like wrecking balls, the consequences swift, hard, and unforgiving. We have great women’s advocacy groups, with great leaders, but we, as women, don’t hold politicians accountable. We don’t have a functional women’s movement. We need to change that, consolidate our power and shape the national debate. We need to be forceful. We need to be heard.

Off the Sidelines

Off the Sidelines